Original Joshua Sokol Jizhi Club

introduction

"It’s hard to extinguish the lights when the rain blows, and the wind blows more brightly. If you fly up, it will be a moon star. " A poem "Ode to Fireflies" by Li Bai shows his infinite reverie of comparing fireflies to starlight. When it comes to fireflies, we may think of the starlight in the shade on a summer night, or the shimmer among the quiet treetops. Have you ever been curious about this kind of creature that gleams slightly? What are the mechanisms and laws behind their flashing? Recently, Orit Peleg, a computational biologist from the University of Colorado, and his team independently developed a high-precision 360-degree camera and triangulation method, which clearly recorded the flash data of different firefly species scattered everywhere. Through these data, Peleg discovered the mystery of synchronous flashing of fireflies of specific species, and also recorded the strange synchronous state that is rare in nature.

Research areas: synchronization, self-organization, group behavior, emergence.

Joshua Sokol | Author

Niu xiaojie | translator

Deng Yixue | Editor

1. Synchronous flashing fireflies

In Japanese folk tradition, fireflies symbolize the departed soul or silent and surging love; In some indigenous cultures in the Andes of Peru, it is regarded as the eye of the ghost; In all kinds of western cultures, fireflies and other luminous insects have been associated with dazzling metaphors, and even these metaphors are contradictory: childhood, crops, bad luck, elves, fear, pastoral, love, luck, death, fornication, summer solstice, stars, words (Stefan Ineichen, 2016) …

Physicists pay attention to fireflies for the same mysterious reason: records show that among more than 2,200 firefly species scattered around the world, a few have the ability to blink synchronously. In Malaysia and Thailand, mangroves covered with fireflies will flash with the beat like Christmas lights; Every summer in Appalachia, fields and forests will be rippling with fluorescent waves that look a little gloomy. In addition to attracting fireflies’ spouses and a large number of viewers, this fluorescent performance show also inspired human beings’ initial attempt to explain the phenomenon of synchronization-that is, the alchemy of magical synergy from very simple elements. In ancient Europe, fireflies were once called "alchemists" because they could shine: perhaps they didn’t really turn other metals into gold, but they did create light strangely. )

Orit Peleg remembers her first encounter with fireflies. It was in the textbook of Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (written by mathematician Steven Strogatz) that she used, and fireflies appeared as one of the examples of "how to synchronize simple systems". At that time, Peleg had never even seen fireflies, which were not common in her hometown of Israel.

"It’s so beautiful that I can’t forget it even after many years." But when Peleg tried to apply computational methods to biological research at the University of Colorado and Santa Fe Institute, she found that although fireflies inspired many mathematical studies, there were few quantitative data describing the actual actions of insects.

Orit Peleg (left), a computational biologist at the University of Colorado, and Raphaël Sarfati, a postdoctoral fellow in her laboratory, have developed a complex system for capturing high-resolution data about firefly flashes in the wild. | Source: Glenn Asakawa

Orit Peleg (left), a computational biologist at the University of Colorado, and Raphaël Sarfati, a postdoctoral fellow in her laboratory, have developed a complex system for capturing high-resolution data about firefly flashes in the wild. | Source: Glenn Asakawa

So she began to solve the problem. In the past two years, a series of papers in Peleg laboratory have collected synchronous data of multiple firefly species in multiple locations, and the clarity is much higher than that of previous biologists. Bard Ermentrout, a mathematical biologist at the University of Pittsburgh, described these research results as "quite surprising"; "I was shocked," said Andrew Moiseff, a biologist at the University of Connecticut.

The paper shows that the real firefly group behavior is not as idealized as in periodicals and textbooks for decades. For example, almost all models of firefly synchronization assume that each firefly has its own "metronome". However, the preprint released by Peleg Lab in March this year shows that not all fireflies have their own metronomes. For fireflies without metronome, the collective beat will only appear when many fireflies gather (Sarfati, R. et al., 2022). In addition, Peleg also recorded a rare type of synchronization [1], which mathematicians call "chimera state". In reality, unless it is a well-designed experiment, this type of synchronization is almost never observed in the natural state (Bansal, K. et al.).

Biologists hope to find new ways to reshape the science of fireflies and call for their protection. At the same time, when mathematicians try to construct synchronization theory similar to that in Steven Strogatz’s textbook, there is not much feedback from synchronous creatures such as fireflies to get real data. "This is a big breakthrough," said Strogatz, a professor of mathematics at Cornell University. "Now we can start trying to get through the obstacles between biologists and mathematicians about fireflies."

2. Synchronization evidence that is difficult to capture

For centuries, the record of firefly synchronization in Southeast Asia has gradually penetrated into the western scientific context. In Malaysia, fireflies called kelip-kelip (flashing onomatopoeia) can live in groups in trees by the river. In 1857, a British diplomat who was traveling in Thailand wrote: "They echo each other, and the light flashes and goes out. In an instant, every leaf and branch was decorated with a diamond-like fire. " (Gudger, E. W., 1919)。

Not everyone can agree with these records. In 1917, in a letter to Science magazine, someone objected: "It is against the laws of nature that such a phenomenon occurs in insects." He believes that this seemingly obvious synchronization effect is caused by the viewer’s involuntary blinking. However, in 1960s, this fact, which had long been known by local people in mangrove swamps, was confirmed by firefly researchers through quantitative analysis.

The firefly of Photinus carolinus species is one of the few known species that flash synchronously. This photo of fireflies is composed of several 30-second shutter exposure photos. | photography: Jason Gambone

The firefly of Photinus carolinus species is one of the few known species that flash synchronously. This photo of fireflies is composed of several 30-second shutter exposure photos. | photography: Jason Gambone

A similar scene was staged in the 1990s, when Lynn Faust, a naturalist in Tennessee, read the confident assertion of Jon Copeland, a scientist, that "there are no synchronized fireflies in North America". Faust knew at that time that what he had observed in the nearby Woods for decades was remarkable.

Faust invited Copeland and Moiseff (collaborators) to see a species called Photinus carolinus (P. carolinus) in the Great Smoky Mountains. Male fireflies are filled with forests and open spaces, suspended at a height similar to that of human beings. These fireflies are not intensive cooperative flashes, but give off a quick flash in a few seconds, then keep quiet for several times this time, and then make the next quick flash. Imagine a similar scene in which a group of paparazzi are waiting for a star to appear. They just take a series of photos quickly every time a star appears, and then fiddle with their fingers in their spare time.

Copeland and Moiseff’s research shows that a single P. carolinus firefly does try to flash with fireflies or LED lights in a nearby jar. The team also placed high-sensitivity cameras on the edge of surrounding fields and forest clearing to record flashes. Copeland looked at the video frame by frame and calculated the number of fireflies shining at each moment. The statistical results show that the fireflies in the field of view of the camera do flash at regular and interrelated time intervals.

Twenty years later, Peleg and her postdoctoral physicist Raphaël Sarfati had better technology to collect firefly data. They designed an image capture system consisting of two GoPro cameras separated by several feet. These cameras can shoot 360-degree videos, so they can capture the dynamics of fireflies from the inside rather than just from the side. The method of calculating firefly flash is no longer frame by frame by hand, but an algorithm developed by Sarfati-recording the flash time and three-dimensional spatial position by triangulation of firefly flash.

In June 2019, Sarfati brought this capture system into the field for the first time in Tennessee to find P. carolinus fireflies. Before that, he had imagined a dense picture similar to the synchronized flashing of fireflies in Asia, but the scene in Tennessee was even more chaotic. This was the first time he saw this scene with his own eyes-there were as many as 8 rapid flashes in about 4 seconds, repeated every 12 seconds. But this chaos is exciting. As a physicist, Sarfati thinks that a highly fluctuating system is more informative than an orderly system. He said: "It’s complicated, even chaotic, but very beautiful."

3. Random and echoing flashes

When Peleg studied firefly synchronization in college, she first understood this phenomenon through the Kuramoto model established by Japanese physicist Yoshiki Kuramoto based on the early work of theoretical biologist Art Winfree. It is the originator of explaining the mathematical mechanism of synchronization phenomenon, and it can be used to describe the synchronization phenomenon in both human cardiac pacing cells and alternating current.

In general, the synchronization system model needs to describe two processes. One is the dynamics of isolated individuals. That is, if there is only one lonely firefly in the jar, how does its own physiological structure and behavior rules determine its flash? The other is what mathematicians call coupling, that is, how the flash of one firefly affects the flash behavior of other fireflies adjacent to it. With the ingenious combination of these two processes, the noise from different fireflies can be quickly adjusted into a neat chorus.

Yoshiki Kuramoto, a professor of physics at Kyoto University, established the most famous synchronization model in 1970s, and jointly discovered chimera state in 2001. | Source: Tomoaki Sukezane

Yoshiki Kuramoto, a professor of physics at Kyoto University, established the most famous synchronization model in 1970s, and jointly discovered chimera state in 2001. | Source: Tomoaki Sukezane

In the Tibetan model, each firefly is regarded as a vibrator with an inherent preference for rhythm. Imagine: there is a hidden pendulum in the firefly that swings steadily, and the firefly flashes every time the pendulum sweeps its arc bottom. Suppose it will move its pendulum forward or backward a little after seeing the flash of a nearby firefly. Even if fireflies are unsynchronized at first, or their preferred internal rhythms are different, in this model, the last group tends to converge on a coordinated flashing pattern.

Over the years, there have been several variants of this model, and each variant has adjusted the rules of internal dynamics and coupling process. In 1990, Strogatz and his colleague Rennie Mirollo at Boston College proved that if a group of simple firefly-like oscillators are related to each other, they will almost always synchronize regardless of the number. In the second year, Barderment Trout described the process of synchronization of Pteroptyx malaccae firefly population in Southeast Asia by accelerating or slowing down the internal oscillation frequency. Just in 2018, the research team of Gonzalo Marcelo Ramírez-Ávila of San Andreas University designed a more complicated mechanism: fireflies switch back and forth between "charging" and "discharging" States, and they will flash during the process.

However, when Peleg and Sarfati’s cameras started capturing 3D data from Photinus carolinus fireflies in 2019, their analysis revealed a new pattern.

One of them is to confirm what Faust and other firefly biologists have mentioned for a long time: a bunch of flashes often start in one place and then cascade and spread in the forest at a speed of half a meter per second. This contagious ripple shows that the coupling of fireflies is neither global (the whole group is related) nor purely local (each firefly only cares about its neighbors). On the contrary, fireflies seem to pay attention to other fireflies at different distances. Sarfati said that this may be because fireflies can only see flashes that occur in a continuous line of sight, while in forests, vegetation often blocks their sight.

P. carolinus fireflies do not seem to meet the core premise of the Tibetan model: unlike Southeast Asian fireflies, P. carolinus fireflies in Tennessee do not have such a cycle. When Peleg and Sarfati put a P. carolinus firefly in the tent, it flashed randomly and didn’t follow any beat. "Sometimes it flashes after waiting for a few seconds, and sometimes it waits for a few minutes," Strogatz said. "This is beyond the scope of existing models."

However, once the research team put in more than 15 P. carolinus fireflies, the swarm in the whole tent showed a collective flash with an interval of several tens of seconds. This synchronization and periodicity is only the result of firefly aggregation. In order to find out how this happened, Peleg’s team asked physicists Srividya Iyer-Biswas from Purdue University and Santa Fe Institute. Soon, Kunaal Joshi, a doctoral student at Iyer-Biswas, analyzed the data they collected on the spot and developed a new periodic emergence model. The detailed paper has been uploaded to the preprint (Sarfati, R., 2022).

Topic: Emergency Periodicity in the Collective Synchronous Flashing of Fireflies.

Address: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.03.09.483608v1.

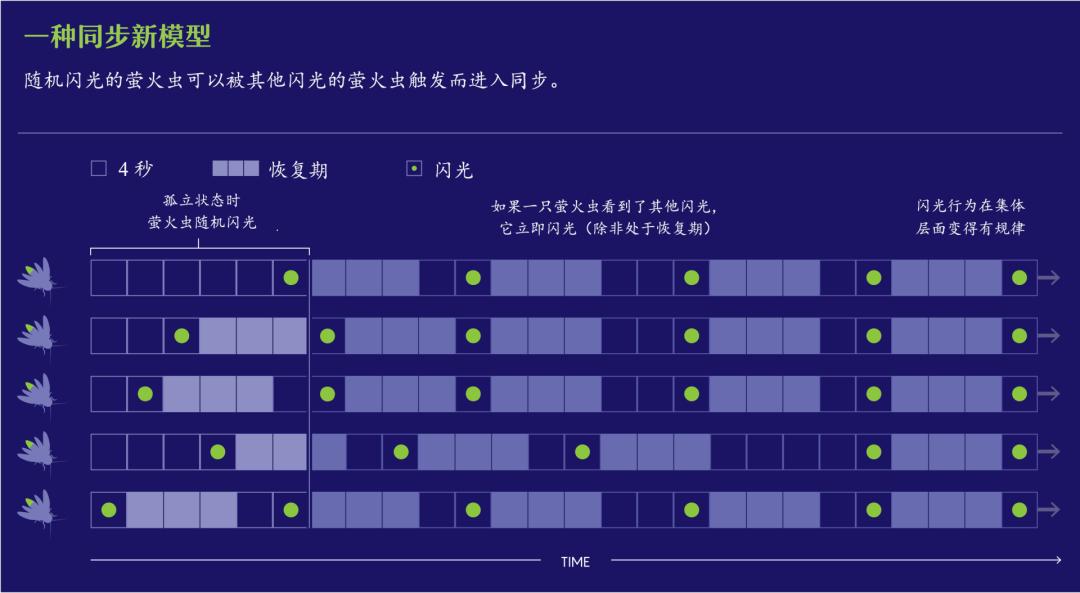

Imagine a lonely firefly flashing and following the rules: if it is sealed now, it will wait for a random time interval and then flash again. However, fireflies need to "charge" their light organs, so there is a shortest waiting time (recovery period). It is also easily influenced by its peers: if it sees another firefly flashing, it will flash immediately as long as its physical conditions permit.

Merrill Sherman/ cartography, translated by Niu Xiaojie/.

Merrill Sherman/ cartography, translated by Niu Xiaojie/.

If there is a large firefly in the silent darkness now, it will be followed by a flash. Each firefly randomly chose a waiting time longer than the recovery period. However, whoever flashes first will inspire all other fireflies to flash immediately. Every time the environment gets dark, the whole process repeats itself. With the increase in the number of fireflies, at least one firefly will randomly choose to flash again when the body allows, which will trigger other fireflies to flash. Therefore, the time between two flashes will be shortened to the recovery period. Researchers who carefully observe this scene will see a stable group rhythm: that is, from flash to darkness, and then suddenly flash from darkness.

Peleg’s second preprint found another peculiar pattern (Sarfati, R., & Peleg, O. ,2022). In Congari National Park, South Carolina, when her team used equipment to record the synchronization of fireflies of Photuris frontalis species, Peleg noticed some strange phenomena: "I caught a small firefly out of time, but it was still punctual."

Topic: chimera States among synchronous fireflies

Address: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.12.491720v2.

The analysis shows that although most firefly "choirs" are flashing rhythmically, the stubborn outliers refuse to cooperate. These outliers are in the same space, flashing according to their own cycle, which is not commensurate with the rhythm of the surrounding "symphony". Sometimes, these outliers seem to be synchronized; Sometimes they just blink randomly, regardless of each other. Peleg’s research group described this as a chimera state, which is a form of synchronization. It was first pointed out by Kuramoto and his postdoctoral fellow Dorjsuren Battogtokh in 2001 (Kuramoto, Y., & Battogtokh, D., 2002), and analyzed by Strogatz and Northwestern University mathematician Daniel Abrams in a mathematical idealized form in 2004. Some neuroscientists’ research shows that this strange synchronization state in brain cell activity has been seen under some experimental conditions, but other than that, it has not been observed in nature so far (Bansal, K., et al., 2019).

The earliest study on chimera state

Thesis title: Coexistence of coherence and inheritance in non-locally coupled phase oscillators.

Address: https://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0210694.

At present, it is not clear why nature prefers this "hodgepodge" synchronization to the unified synchronization form. However, this basic synchronization phenomenon also constitutes an evolutionary mystery: how does this aggregation help male individuals stand out from potential spouses? Peleg thinks that we should not only study the behavior patterns of male fireflies, but also pay attention to female fireflies. Her research team has begun to study the firefly P. carolinus, but has not studied the species P. frontalis which is prone to chimera state.

4. Fireflies and Computer Science

For the model, it is now necessary to encapsulate the observed firefly patterns in a new or improved framework. Ermentrout’s paper, which is still under review, provides a unique mathematical description of Photinus carolinus fireflies: suppose these insects are noisy and irregular oscillators instead of waiting for purely random time beyond the minimum recovery time required? In this way, fireflies may flash periodically only when they gather. In computer simulation, this model is also consistent with Peleg’s data. Ermentrout said: "Although we didn’t write it out in a program, there were still fluctuations and so on."

Biologists say that Peleg and Sarfati’s cost-effective camera and algorithm system are very helpful to promote firefly research and make it popular. Fireflies are difficult to study in the wild, because it is difficult for the public to distinguish species by their flashes except the most dedicated researchers and hardcore enthusiasts. Therefore, although people are worried that many firefly species are becoming extinct, it is still relatively difficult to measure the range and abundance of firefly population. Peleg’s work can make it easier to collect, analyze and share firefly flash data.

In 2021, Sarfati used this system to confirm a report from Arizona: local Photinus knulli firefly species can synchronize when the aggregation number is enough. This year, Peleg Lab sent 10 copies of camera images to firefly researchers all over the United States. In order to promote species protection, machine learning researchers in Peleg Lab are trying to develop an algorithm to identify firefly species from video flash patterns.

Fireflies have inspired the development of mathematical theory for decades; Peleg hopes that these more subtle truths discovered now will have a similar impact. Moiseff has the same wish. He said that fireflies "were already doing computer science before we humans appeared." Understanding their synchronization mechanism can help us better grasp the self-organizing behavior of other organisms.

references

[1] link: https://www.quantamazine.org/physicists-discover-exotic-patterns-of-synchronization-20190404/

[2] Stefan Ineichen (2016). Light into Darkness: The Significance of Glowworms and Fireflies in Western Culture. Advances in Zoology and Botany, 4(4), 54 – 58. DOI: 10.13189/azb.2016.040402.

[3] Sarfati, R., Joshi, K., Martin, O., Hayes, J., Iyer-Biswas, S., & Peleg, O. (2022). Emergent periodicity in the collective synchronous flashing of fireflies. bioRxiv.2022.03.09.483608, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.09.483608

[4] Sarfati, R., & Peleg, O. (2022). Chimera States among Synchronous Fireflies. bioRxiv 2022.05.12.491720; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.12.491720

[5] Bansal, K., Garcia, J. O., Tompson, S. H., Verstynen, T., Vettel, J. M., & Muldoon, S. F. (2019). Cognitive chimera states in human brain networks. Science Advances, 5(4), eaau8535.

[6] Gudger, E. W. (1919). A Historical Note on the Synchronous Flashing of Fireflies. Science, 50(1286), 188–190. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1643069

[7] Kuramoto, Y., & Battogtokh, D. (2002). Coexistence of Coherence and Incoherence in Nonlocally Coupled Phase Oscillators. Nonlinear Phenomena in Complex Systems, 5(4), 380-385.

This article is translated from Quanta Magazine.

Title of the article: How How Do Fireflies Flash in Sync? Studies Suggest a New Answer

Article link: https://www.quantamazine.org/how-do-fireworks-flash-in-sync-studies-suggest-a-new-answer-20220920/

Latest papers on complex science

Since the express column of papers in the top journals of Chi Zhi Ban Tu was launched, it has continuously collected the latest papers from top journals such as Nature and Science, and tracked the frontier progress in complex systems, network science, computational social science and other fields. Now the subscription function is officially launched, and the paper information is pushed through the WeChat service number "Chi Zhi Ban Tu" every week.

Original title: "Synchronous flicker of fireflies: how to emerge order in randomness?" 》